|

| |

Bodywork Basics page 2 Bodywork Basics page 2

|

Macy's Garage, Ltd.

America's BEST

Triumph Shop! |

There appears to be many folks out there

who think that paint will hide minor bodywork flaws, and only find out after the

paint has been applied that it magnifies even the tiniest imperfection. To

achieve flawless paint, the underlying surface must be flawless as well.

Beating crumpled metal out with a hammer and smearing a thick layer of bondo

over the whole mess is never going to look right, and it probably isn't going to

last either! Follow along as we create a perfect surface to hold the paint

on the TR3B apron.

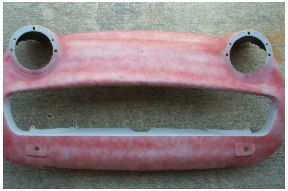

Once

all of the metalwork had reached the point of diminishing returns, the first

layer of epoxy primer was sprayed on. Epoxy primers are expensive, but

they grip bare steel like there's no tomorrow, and I've found it to be the

prefect foundation for long paint life. Yes, it's back on the car

again for another 'fitting'. Once

all of the metalwork had reached the point of diminishing returns, the first

layer of epoxy primer was sprayed on. Epoxy primers are expensive, but

they grip bare steel like there's no tomorrow, and I've found it to be the

prefect foundation for long paint life. Yes, it's back on the car

again for another 'fitting'. |

While

bolted to the car to hold the apron's shape, a thin layer of premium filler

was applied to any 'low' areas we could see or feel. The 1st layer of

epoxy primer needs to be sanded with 120 grit before the filler is applied,

to promote adhesion. While

bolted to the car to hold the apron's shape, a thin layer of premium filler

was applied to any 'low' areas we could see or feel. The 1st layer of

epoxy primer needs to be sanded with 120 grit before the filler is applied,

to promote adhesion. |

Careful

sanding with both air sanders and by hand removed most of the filler that

was applied in the last photo, leaving a super thin layer to level out some

of the light waves, probably no thicker than a manilla file folder. Careful

sanding with both air sanders and by hand removed most of the filler that

was applied in the last photo, leaving a super thin layer to level out some

of the light waves, probably no thicker than a manilla file folder. |

A

second layer of epoxy primer is applied over the entire apron, sealing the

thin filler between two layers of epoxy. This is a relatively new

approach to filler application which has been made possible by modern

chemistry. Old time body guys will give you an argument about this,

but it's really the best method for today's products. A

second layer of epoxy primer is applied over the entire apron, sealing the

thin filler between two layers of epoxy. This is a relatively new

approach to filler application which has been made possible by modern

chemistry. Old time body guys will give you an argument about this,

but it's really the best method for today's products. |

Next

we apply glazing or "spot putty" to any pin holes in the original filler,

and tiny dimples which might be visible. This putty is very thin and

creamy, and not only spreads easily, but sands easily too. You'll take

forever trying to get normal filler perfect, so this is the easy way to

bring your bodywork up another notch. Next

we apply glazing or "spot putty" to any pin holes in the original filler,

and tiny dimples which might be visible. This putty is very thin and

creamy, and not only spreads easily, but sands easily too. You'll take

forever trying to get normal filler perfect, so this is the easy way to

bring your bodywork up another notch. |

Almost

all of the spot putty sands back off, but be careful that you don't go

through the epoxy and expose any bare metal. This will most likely

happen if you left a high spot during the metalworking phase, which should

have been caught and corrected before this point. Almost

all of the spot putty sands back off, but be careful that you don't go

through the epoxy and expose any bare metal. This will most likely

happen if you left a high spot during the metalworking phase, which should

have been caught and corrected before this point. |

Now

is the time to get serious with your sanding. We used a light gray 2K

primer, applied for high-build, and then sprayed a light red guide coat all

over. If you noticed all of the different colors we've used, it's done

on purpose to provide a visual reference. Now

is the time to get serious with your sanding. We used a light gray 2K

primer, applied for high-build, and then sprayed a light red guide coat all

over. If you noticed all of the different colors we've used, it's done

on purpose to provide a visual reference. |

From

this point forward, all sanding must be done with a block of some sort,

using progressively finer sandpaper. This photo shows about half of

the various sanding blocks I have, and I use them all depending on the shape

of the body panel I'm working. This should always be done wet, and I like to

put a few drops of dishwashing soap into the water, just to help keep the

sandpaper clean. From

this point forward, all sanding must be done with a block of some sort,

using progressively finer sandpaper. This photo shows about half of

the various sanding blocks I have, and I use them all depending on the shape

of the body panel I'm working. This should always be done wet, and I like to

put a few drops of dishwashing soap into the water, just to help keep the

sandpaper clean. |

When

you use a sanding block and a guide coat, you can see the low spots quite

easily. Note the dark black spot where the epoxy has been exposed, so

you can't sand this area any more to level out the low next to it. Experience

will tell you whether you need to apply spot putty in the low, or if another

layer of high build primer will take care of it. When

you use a sanding block and a guide coat, you can see the low spots quite

easily. Note the dark black spot where the epoxy has been exposed, so

you can't sand this area any more to level out the low next to it. Experience

will tell you whether you need to apply spot putty in the low, or if another

layer of high build primer will take care of it. |

When

you reach the point that block sanding the high build primer removes all of

the guide coat, the part will be straight. You should be down to 400

grit sandpaper by now, and a final layer of thin (not high build) 2K primer

should be applied and blocked with 600 in final preparation for paint.

Time to mix the color! When

you reach the point that block sanding the high build primer removes all of

the guide coat, the part will be straight. You should be down to 400

grit sandpaper by now, and a final layer of thin (not high build) 2K primer

should be applied and blocked with 600 in final preparation for paint.

Time to mix the color! |

And

here's the finished product, an apron that looks and fits better than before

the accident. About 40 hours were needed to straighten and repair this

apron. Expensive? Absolutely! But still about $1000 less

than a new reproduction, and the best part is that it fits the car like it

was made for it. Oh!, that's right, it was! And

here's the finished product, an apron that looks and fits better than before

the accident. About 40 hours were needed to straighten and repair this

apron. Expensive? Absolutely! But still about $1000 less

than a new reproduction, and the best part is that it fits the car like it

was made for it. Oh!, that's right, it was! |

Here's

a beauty shot the Editor took when he got the car home. Notice the cut

out areas under the bumper, along the lower edge of the apron. This is

why we took the time to fix them correctly! Here's

a beauty shot the Editor took when he got the car home. Notice the cut

out areas under the bumper, along the lower edge of the apron. This is

why we took the time to fix them correctly! |

So there you have it, a good example of the many steps required

to properly restore one abused body panel. While this particular

piece needed just about everything imaginable to save it, if you multiply this

process by 4 fenders, 2 doors, a hood and a trunk lid, not to mention repairs to

the basic body structure itself, you can begin to understand why vintage auto

restoration is such an expensive endeavor!

Back to Bodywork Basics page 1

|

Bodywork Basics page 2

Bodywork Basics page 2 Here's

a beauty shot the Editor took when he got the car home. Notice the cut

out areas under the bumper, along the lower edge of the apron. This is

why we took the time to fix them correctly!

Here's

a beauty shot the Editor took when he got the car home. Notice the cut

out areas under the bumper, along the lower edge of the apron. This is

why we took the time to fix them correctly!